Douglas Trumbull

1942-2022

When he passed in 2022, Douglas Trumbull had been working for over a decade on his next-generation cinematic format titled Magi, capturing footage in 3D at 120 frames per second, presented in the Magi Dome, a 20-foot tall, dome-shaped theater, equipped with a deeply curved, hemispheric screen that wraps around the audience, filling their peripheral vision.

“I’m trying to make a movie in this(format) because my whole mental set is how to make an immersive movie experience…which started with Stanley Kubrick. When he was working in 70 millimeter, immersive Cinerama, there were these 90 to 100-foot-wide screens in theaters back in those days. They’re not around anymore.”(A1)

Stanley Kubrick first encountered Trumbull’s work at the 1964 World Fair in New York, when he saw 'To the Moon and Beyond', a spaceflight film projected onto a massive “Moon Dome”, on which a 21-year old Trumbull had worked as an illustrator.

Kubrick was so impressed by the experience that he hired its production company, Graphics Films, to assist in the pre-production of his upcoming science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Magi Dome Theater

“I’m trying to make a movie in this(format) because my whole mental set is how to make an immersive movie experience…which started with Stanley Kubrick. When he was working in 70 millimeter, immersive Cinerama, there were these 90 to 100-foot-wide screens in theaters back in those days. They’re not around anymore.”(A1)

Stanley Kubrick first encountered Trumbull’s work at the 1964 World Fair in New York, when he saw 'To the Moon and Beyond', a spaceflight film projected onto a massive “Moon Dome”, on which a 21-year old Trumbull had worked as an illustrator.

Moon Dome at the 1964 World Fair

Kubrick was so impressed by the experience that he hired its production company, Graphics Films, to assist in the pre-production of his upcoming science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

A few months later, Kubrick decided to move the entire production to London, and Trumbull found himself scrambling for a job, “I got laid off. The contract was over and he was going to make it somewhere else.

I said, “This sounds like a good deal, I want to get in on this movie.” I called my boss Con Pederson and I said, “I want to work on this movie, how do I contact this Kubrick guy?”

He said “I have this contract, I can’t talk about it, I have a nondisclosure agreement,” but I didn’t so I said,

I said, “This sounds like a good deal, I want to get in on this movie.” I called my boss Con Pederson and I said, “I want to work on this movie, how do I contact this Kubrick guy?”

He said “I have this contract, I can’t talk about it, I have a nondisclosure agreement,” but I didn’t so I said,

“I’m not under contract and I’m unemployed, please help me out Con.”

So he said, “Well, Kubrick’s phone number is penciled in the corner of the bulletin board downstairs in the office.” Literally, that was the connection. I didn’t even work there, but I went in the back door, because there wasn’t any security at the time, I find this little phone and I cold call Stanley Kubrick and say, “I’ve been working on these drawings and I want a job,” and he said “Okay.” He bought me a plane ticket and I went over there.

“So I’m there, I’m just this young guy. I was never even involved with the camera department at Graphic Films, I was just doing these illustrations…And that was my beginning of my transformation of having to learn about photography and having to learn new and different ways to solve these problems and having the support of Stanley Kubrick who said, “Yeah, get the animation camera, you need a piece of glass? Get it. You need a light? Get it. You need to go downtown to buy a bunch of lithograph materials? Go.” This led to this process of creative things, technical solutions, photography and art, all going on simultaneously. I was 23. It was an incredible break, but I was the right guy for the job.”(A15)

As the years passed and the production continued on, Trumbull’s responsibilities grew wider and greater, culminating in him crafting the iconic Stargate sequence at just 25 years old.

So he said, “Well, Kubrick’s phone number is penciled in the corner of the bulletin board downstairs in the office.” Literally, that was the connection. I didn’t even work there, but I went in the back door, because there wasn’t any security at the time, I find this little phone and I cold call Stanley Kubrick and say, “I’ve been working on these drawings and I want a job,” and he said “Okay.” He bought me a plane ticket and I went over there.

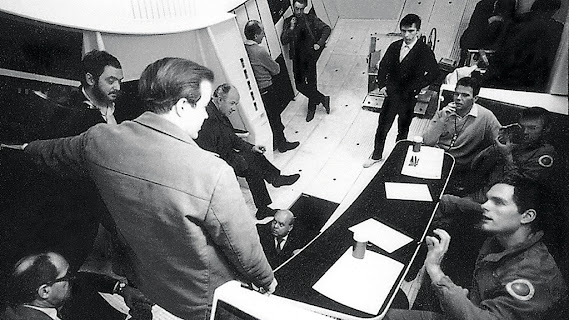

Trumbull and Kubrick on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey

“So I’m there, I’m just this young guy. I was never even involved with the camera department at Graphic Films, I was just doing these illustrations…And that was my beginning of my transformation of having to learn about photography and having to learn new and different ways to solve these problems and having the support of Stanley Kubrick who said, “Yeah, get the animation camera, you need a piece of glass? Get it. You need a light? Get it. You need to go downtown to buy a bunch of lithograph materials? Go.” This led to this process of creative things, technical solutions, photography and art, all going on simultaneously. I was 23. It was an incredible break, but I was the right guy for the job.”(A15)

As the years passed and the production continued on, Trumbull’s responsibilities grew wider and greater, culminating in him crafting the iconic Stargate sequence at just 25 years old.

Stargate Sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey

Throughout his entire career, Trumbull would reference how Kubrick’s attempt to “change the form” with 2001 shaped his perspective on cinema, “Kubrick said “You know, I can actually change the way I direct. I don’t have to do over-the-shoulder shots and stupid melodrama and the actors’ dialogue and explain everything. I can just show it and it will be immersive.” And he started extracting shots out of the movie. Because he said “I want the audience to feel like they’re in space. I don’t want to tell a story about Keir Dullea in a pod, I want to tell a story about you being in space.”(A1)

“That’s where Kubrick profoundly affected me in terms of what could be the future of cinema- or a future of cinema, an immersive art form where the director has to consciously decide to allow the audience to participate and be present in the situation.”(A2)

According to Trumbull, this required the massive, curved screens of Cinerama theaters, “He felt a responsibility because he was one of very few filmmakers that was actually asked and authorized to make a Cinerama movie. This was 90-foot wide screens—unheard of today—and these big, deeply curved special Cinerama theaters. And he said, “I feel a responsibility. I’ve gotta take people on this trip.”(A10)

After directing his first feature film titled Silent Running in 1973, Trumbull partnered up with another special effects talent, Richard Yuricich, to form Future General Corporation in 1975.

Trumbull and Yuricich on the miniature set of Blade Runner

Funded by Paramount, FGC was an endeavor to improve the technology used to make films. Within the first 9 months of its existence, Trumbull states, “We invented Showscan. We invented the first simulator ride. We invented the 3D interactive video game. And we invented the Magicam process(an early version of live compositing, as seen on Carl Sagan’s Cosmos).”(A4)

Building off the engineering work at Future General, Trumbull designed his second feature film, Brainstorm, around their newly developed, high frame rate format called Showscan, a 70mm film format projected at 60 frames per second.

Showscan became the first of it's time, as nearly all films since the dawn of sound have been presented at 24 frames per second. Showscan offered an image with remarkably less motion blur and four times the resolution of conventional film. Today, one may recognize high frame rates in video games and sports television broadcasts, employed to give the viewer a smoother, more detailed experience.

A Showscan Camera in Film as Experience - 1987

Showscan found itself a passionate and devoted following, including famous movie critic Roger Ebert, who happily used his platform to promote Trumbull’s efforts, calling Showscan the most realistic film process ever demonstrated, “Trumbull created a picture so incredibly high in quality that the screen seemed to be a transparent window revealing an actual image.”(A17)

Heavyweight Hollywood directors like John Badham(Saturday Night Fever) and Tony Scott(Top Gun) endorsed Showscan, Richard Donner(Superman) once saying “At this point, I know of nothing else that is as exciting, as inventive, as creatively stimulating as Showscan”(A3)

Unfortunately, despite presenting this advanced film format all over the industry, gaining acclaim from both the studios and filmmakers, Trumbull wasn’t able to get Showscan installed in cinemas, “There was this kind of business problem which was that the theaters said, “We’re not going to put in a bunch of projectors to show this movie unless all the movies from Hollywood are made in Showscan…The studios said we all love it but we’re not gonna do it unless all the theaters will show it, so it was kind of a catch-22 that no one would put their foot forward and make the commitment to start transforming the movie industry into a higher frame rate technology…so I couldn’t get that to happen and I had to make Brainstorm conventionally.”(A12)

Still, Trumbull was far from giving up on the technology he had developed, leaving feature filmmaking to craft projects exclusively in Showscan, “I could easily make a regular motion picture and I’ve had many offers to make regular motion pictures, but I am so convinced now that it’s possible to make a totally new kind of motion picture in Showscan that that’s the only way I want to work.”(A13)

In 1983 Trumbull developed New Magic, a 22-minute short film showcasing the realistic effect of Showscan. In 1986 Trumbull presented Showscan to the public at the World’s Fair in Vancouver and in 1987 released a documentary covering his personal film journey and the many advocates of Showscan, titled Film as Experience. He continued for over a decade to campaign for this format, insisting it was the natural next step for cinema, “It took 13 years to get paper diapers launched in this country. It took somewhere between 7 and 10 years to get zippers put on clothing. I’m very used to the idea that this is a natural process we’re going through here. It does take time for people to see it, get used to it…it takes a while to gather consensus.”(A13)

The struggle to get Showscan installed in cinemas continued into the 90s before there came a unique opportunity for Trumbull to work with another one of his inventions, the motion-based Ridefilm, when Steven Speilberg hired him to direct Back to the Future: The Ride at Universal Studios Orlando.

Behind the scenes of Back to the Future Ride Miniatures

“It was kind of the ultimate immersive experience that brought together giant screen IMAX dome projection, photographic effects, special cameras, the whole idea of motion-based entertainment.”(A5)

“To me, the Back to the Future ride was a really major experiment in cinematic immersion….For the first time the screen is not just here…it’s all around you…”(A11)

A patent diagram depicting the ride film technology

“The shocking thing to me was that it was never reviewed or considered by the film industry as a leap of cinematic potential, it was just dismissed as a theme park attraction.”(A2 )

Soon after completing Back to the Future: The Ride in 1991, Trumbull was hired to craft an even more ambitious, high-tech cinematic experience for the brand new, pyramid-shaped Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas.

“This is the first time that anybody’s ever said to me, ‘You could design the whole thing.’ and not only the concept of the shows and the production of the shows but the design of the theaters themselves.”(A8)

The Luxor Pyramid under construction in Las Vegas

After being denied the projector brightness and 30fps frame rate he wanted for Back to the Future, Trumbull was now able to craft visuals in stereoscopic 3D at 48 frames per second, leaps beyond anything seen at the time.

Architect Gregory Beck would later reflect on his transformative experience working on the Luxor Hotel; “My career changed when Doug asked me to design three special venue theaters for Luxor Las Vegas. Not surprisingly, each featured one of his brilliant inventions- the Ride-film, a Showscan virtual stage set, and an impossibly steep vertical screen theater.”(A9)

Titled “Secrets of the Luxor Pyramid”, the three-part story centered around the discovery of a magical obelisk in a fictional dig site under the Luxor Hotel.

Riders in-line for In Search of the Obelisk

The first part of the experience, In Search of the Obelisk, functioned much like the Back to the Future ride. Riders are towed through a secret excavation lab under the Luxor, dragged into a chase as the precious obelisk is stolen, pushing riders through time and space itself.

The Luxor Live stage and 3D screens

The second installment, Luxor Live, was a parody of television talk shows, where the actors from In Search of the Obelisk appear live, performing on a stage below a “live feed” of an eclipse over Egypt, which eventually disrupts the show. Audiences were instructed to put on their 3D glasses to view the extended solar eclipse computer graphics(CG) animation.

The Theater of Time

The final part of the attraction trilogy, and the most popular, was titled, The Theater of Time. This was the steepest theater ever designed, seating 350 total, with each row placed 4 feet above the one in front of it, the projector mounted in the center of the middle row. The theater was so steep that each seat was equipped with a safety bar that descended over audience members before the start of the film. The screen was 7 stories high with a 2:1 vertical aspect ratio similar to the smartphone screens of today. The visuals combined masterful miniature work with early CG visuals, depicting three different futuristic Egyptian societies at 48 frames per second, twenty years before the same tech would reach cinemas(and remain on Televison).

Seeing that by the 2000s Trumbull had directed more ride-films than he had feature films, it's easy to doubt how much his ride experience would fit into the standard cinema experience. Trumbull himself insisted the kinesthetic motion in his ride-films was unfit for true cinema, “I wouldn’t call dynamically moving seats dramatic filmmaking and I certainly wouldn’t ask Steven Speilberg or anybody to be involved in a film where the seats are jerking around.”(A13)

Ironically, Trumbull has also compared the last act of Kubrick’s 2001, his primary inspiration, to an amusement park ride, “It became kind of a 60’s light show…being the kind of things they do at a rock and roll concert where they just project all over the walls and ceilings with liquids and stars and strobe lights and all this kind of stuff…it was badly reviewed.

“No one in the normal critical movie reviewing world knew what to make out of this movie. They didn’t understand it at all, and about 30 days into the release of 2001 the studio was ready to abandon the movie and pull the plug. They said nobody gets it. The reviews are bad and there’s nobody in the theater. Until one of the guys at the MGM publicity department said let’s call it ‘The Ultimate Trip’. They rebranded the movie The Ultimate Trip and people started smoking a little pot and going to see it front row….so that was really part of the transformation of people’s understanding of what Kubrick was trying to do as a filmmaker, which was to transport the audience to another dimension”(A11)

Kubrick himself once detailed his approach to 2001, “I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbalized pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophic content. To convolute McLuhan, in 2001 the message is the medium. I intended the film to be an intensely subjective experience that reaches the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does.”(A6)

Despite Trumbull's enthusiasm for technology, he understood that crafting a more immersive experience required a new approach to film language, “As you start implementing these more immersive technologies where the screens get larger and wider, and the image becomes much more realistic and involving, you start heading into this territory that’s like 2001 which was a first-person experience…that an edited, dramatically performed classic movie style, with actors and over-the-shoulders and singles and closeups and all that kinda stuff, which is fine for a lot of movies, but if you’re going into this new territory I think we need to start exploring the language of cinema and how you can tell a different kind of story in a different way.”(A12)

As the years went by and none of his inventions were accepted into the Hollywood ecosystem, Trumbull’s career mission to advance the mainstream theatrical experience appeared to be a failure. Luckily, in 1994, Trumbull merged his Ridefilm company with the IMAX corporation and developed a plan to bring it into the commercial entertainment marketplace, raising over $300M in a successful IPO(A14). Today, IMAX is far and away the most well-known premium format in theaters, “I’m very proud of proving that you can bring a new technology into the mainstream of the movie business…You can actually change the shape of theaters, change the screen size, change the film size. You can do all these things.”(A3)

Trumbull wearing the first IMAX 3D glasses

Another seismic shift came with the industry’s transition into digital projection, in which Trumbull quickly found exciting new engineering opportunities, “I found out that the (digital) projectors are running at 144 frames a second and I said what!?!? 144? That’s twice as much as Showscan was, and you’re doing it already? And there’s thousands of projectors out there that do that?.. Could we do a new frame every flash?”(A3)

Trumbull quickly transitioned his efforts into developing the digital Magi system, “When I found out Christie had developed a mirage 4k projector capable of running 3D at 120 frames per second, I realized it was now time for me to get back to making movies.”(A3)

As he was developing his new digital format, Trumbull began to see popular filmmakers trying their hand at the high frame rate cinema he'd been prophecizing for decades.

Peter Jackson on the set of the Hobbit

Peter Jackson became the first director to have a 3D, high frame rate(HFR) theatrical release with The Hobbit in 2012. Unfortunately, it was widely panned by audiences for looking too smooth, too real, and according to Trumbull, "more like television".

In a 2014 interview, Trumbull addressed this apparent failure of high frame rate cinema, “I can only imagine the kind of meetings that happened between Peter Jackson and the distribution head at Warner Brothers. They did not support the 48 frame thing. Peter paid for it himself. He said, “I really want to do this.” And they said, “You’re on your own, pal.” So he did it and he’s a happy camper all during production because he’s seeing the blurring and strobing is going away and it looks much better…you can acclimate to it to where you don’t think of it as television—you think of it as more clarity.

“Unfortunately, the audience didn’t quite see it that way. They showed a short reel of The Hobbit at CinemaCon(2012) and it got really bad reviews—just attacked viciously. So even though they had arranged for I think about ten thousand theaters to be fully equipped with all the stuff necessary to go 48 or 60 in theaters, the studio pulled the plug and gave them I think 400 theaters with 48 frames.”(A10)

Nonetheless sticking to his decision, Peter Jackson doubled down and released the two remaining Hobbit installments in HFR, “48(frames per second) is a way, way better way to look at 3D. It’s so much more comfortable on the eyes…It was interesting to try to interpret what people’s reaction was.”(B4)

While it seemed like the majority of filmgoers found the HFR distracting and odd, it should be noted that there are still fans of the smooth, crisp HFR look, including Trumbull, "I’ve seen the movie all ways – I’ve seen it in 2D at 24 frames, I’ve seen it in 3D at 24 frames, and I’ve seen it in 3D at 48 frames. And because I’m so adapted to it, I really like the 48 frames."(B14)

Unfortunately, for most people, it proved to be an unnecessary distraction. It’s also worth mentioning that Jackson himself, stepping in late to replace Guillermo Del Toro on the Hobbit movies, admitted he did not have the time in pre-production to meticulously alter his visual approach for this new format, “I spent so much of The Hobbit feeling like I was not on top of it. The fact that I hadn’t had much prep and I was making it up as I went along and even from a script point of view…I hadn’t really gotten the entire scripts all the way through.”(B10)

Several years distant from the Hobbit trilogy, Peter Jackson could reflect on his HFR experience with hindsight, “I was pleased by the time we finished. But it took us the three Hobbit movies to figure out how to color correct it and grade it properly so it didn’t look, you know, the first one wasn’t…We made a lot of changes after the first Hobbit movie, and then the second, and then the third…and then I think we were getting to feeling pretty good towards the end. It’s up to filmmakers and I know that Ang Lee, I believe, is looking at doing a movie in high speed.”(B5)

Ang Lee on the set of Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk

Ang Lee, acclaimed director of Life of Pi and Brokeback Mountain, was the next director to get his film released theatrically in 3D HFR, with both Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk in 2016 and Gemini Man in 2019. These films, much like Trumbull’s Magi system, were shot and presented in 3D at 120 frames per second.

Despite these bold decisions, Lee claims he is not a tech guy, “I cannot hardly use email. My smartphone? I only call out. Zero interest in technology. The opposite of technology. That is me.”

Yet Lee insists that every movie could utilize this tech, “It’s more like how our eyes are designed to see. I think people are so wrong to see 3D and HFR as tricks that only hacks use for action or spectacle. I think it’s the opposite. What 3D gives you is intimacy, and what 3D does best is portray faces. I’m so eager to show that. That’s what 3D is about, not action. We haven’t even gotten there yet.”(B8)

Unfortunately, neither of Lee’s films appear to have changed the opinion of general audiences. Just like with The Hobbit, the high frame rate presentation was criticized for looking “too real”. Instead of immersing viewers in a real space with real people, it gave the impression of watching a bunch of actors in makeup.

Unfortunately, neither of Lee’s films appear to have changed the opinion of general audiences. Just like with The Hobbit, the high frame rate presentation was criticized for looking “too real”. Instead of immersing viewers in a real space with real people, it gave the impression of watching a bunch of actors in makeup.

Trumbull wasn’t afraid to share his harsh opinion of Lee’s use of the technology, despite promoting both Billy Lynn and Gemini Man prior to their releases, “When he became attached to Billy Lynn, he came to view Magi six times with various members of the crew and fell in love with it, but he wanted to go further with it, something he called “the whole shebang.” He decided to shoot with two cameras capturing 120fps for both eyes in sequence and project it with dual Christie projectors at 28-foot lamberts, which was just not possible. There were not screens big enough available to do this. This led to very vivid images, but they looked like video.

“Lee had arranged to screen some battle footage from the flashback scenes at the NAB(National Association of Broadcasters) convention. I was overcome. I mean, I was shaking. It took me about 30 minutes to get a hold of myself afterwards, and I thought, “this is really going to be something.” But it didn’t work out. When I went to the premiere at Loews Theatre in New York, it just wasn’t a good experience.

“The bad press around Billy Lynn hasn’t given HFR a good name; it has certainly pushed back our efforts of what we are trying to do here.”(B9)

“The bad press around Billy Lynn hasn’t given HFR a good name; it has certainly pushed back our efforts of what we are trying to do here.”(B9)

What Trumbull tried to explain to Ang Lee was the way he solved that dreaded soap opera effect, “The problem with digital projectors and televisions is that they have no shutter. If you increase the frame rate and don’t have the shutter, it’s going to look exactly like television. That’s the problem with Gemini Man. I tried endlessly to explain this to Ang Lee over and over again, and he never got it. None of those guys ever understood it. And they put that movie out with no shutter. Digital projectors in movie theaters don’t have shutter. I found that you can actually add a shutter in the DCP copy of the movie with black frames that replicate the shutter. That’s the difference between cinema and television — the shutter. They keep making the same mistake. Peter Jackson made the same mistake with The Hobbit.”(A14)

According to Trumbull, by shooting and projecting with the Magi system, you’d have a high frame rate film without the soap opera effect, evoking something entirely realistic and unique, something Trumbull refers to as “perfect temporal continuity”.

Trumbull posing with a screen of UFOTOG

In order to determine how effective this solution is, one would have to see UFOTOG, Trumbull’s own film crafted for Magi, shot specifically to utilize the immersive image. Trumbull spent a considerable amount of time touring and screening UFOTOG for audiences in 2014, but the 12-minute short is now unavailable, and most likely will never again be showcased in the theater it was designed for. Only a handful of people have been out to Trumbull’s ranch in Massachusetts to see UFOTOG in the Magi Dome theater, including the third and most recent Hollywood director to release a film in HFR 3D, “I don’t know what Jim Cameron is doing with the next “Avatar” movies but I’ve shown him what we do here and he was blown away.”(A14)

Trumbull closely aligned himself with James Cameron under the media spotlight, honoring Avatar as a critical example of what cutting-edge technology can do for audience immersion, “It’s not that I wanna talk about Avatar forever but Avatar created an alternate world. A kind of virtual reality world that would benefit from high frame rates. It would not be diminished by having a super real environment to it that would be beyond television in that kind of texture. Jim Cameron wants to shoot his next film at 48, 60, or 72(frames per second), he’s been very open about it. He’s been very gracious in talking about Showscan and remembering it as the best film process he ever saw…so I think we’re gonna start seeing some upward mobility in a lot of industry experimentation with frame rates in the near future.”(A12)

The similarities between Trumbull and Cameron run deeper than just their passion for advancing film technology, Cameron also refers to 2001: A Space Odyssey as one of his biggest inspirations, "The first lightbulb moment (as a filmmaker) was when I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time, and the lightbulb there was that a movie can be more than just telling a story. It can be a piece of art. It can be something that has a profound impact on your imagination...It sort of just blew the doors off the whole thing for me at the age of 14 and I started thinking about film in a completely different way and got fascinated by it.

"It's also to my knowledge one of the first films that really had a definitive 'making of' book...It was the first one I knew of that was available and I read it from cover to cover 18 times and didn't understand half of it until many years later...but it started a process of projecting myself into the idea of actually creating images using these high tech means."(B16)

James Cameron on the set of Avatar

“We did this big frame rate presentation with 48 and 60. They’re both highly superior to 24. What I think is clear is we’ve gotta get off 24.”(B11)

Cameron at that time was urging the industry to move on from the classic frame rate we’re all accustomed to, whereas in more recent years, perhaps after the reactions to Peter Jackson and Ang Lee’s experiments, has held a more reserved opinion, “I have a personal philosophy around high frame rate, which is that it is a specific solution to specific problems having to do with 3D. And when you get the strobing and the judder of certain shots that pan or certain lateral movement across frame, it's distracting in 3D. And to me, it's just a solution for those shots. I don't think it's a format…I think it's a tool to be used to solve problems in 3D projection. And I'll be using it sparingly throughout the Avatar films.

“To me, the more mundane the subject, two people talking in the kitchen, the worse it works, because you feel like you're in a set of a kitchen with actors in makeup. That's how real it is, you know? But I think when you've got extraordinary subjects that are being shot for real, or even through CG, that hyper-reality actually works in your favor. So to me, it's a wand that you wave in certain moments and use when you need it. It's an authoring tool.”(B6)

“To me, the more mundane the subject, two people talking in the kitchen, the worse it works, because you feel like you're in a set of a kitchen with actors in makeup. That's how real it is, you know? But I think when you've got extraordinary subjects that are being shot for real, or even through CG, that hyper-reality actually works in your favor. So to me, it's a wand that you wave in certain moments and use when you need it. It's an authoring tool.”(B6)

After bringing 3D into the forefront of Hollywood filmmaking with Avatar, many were curious how the director would utilize high frame rates in Avatar 2, “We tried to decide how to apply it and the rule was, whenever they're underwater, it’s 48 frames. Boom. Just don’t even think about it. Some of the flying scenes, some of the broad vistas benefit from 48 frames per second. If it’s just people sitting around talking…it’s not necessary. In fact, it’s actually sometimes even counterproductive because it looks a little too glassy smooth. So the trick to it was to figure out where to use it and where not to use it. Now, the one thing I will say pretty definitively is 48 frames doesn’t benefit a 2D movie very much, if at all.”(B12)

Rereleasing the first Avatar in the months before its sequel, Cameron opted to test this variable frame rate approach, employing Pixelworks’ TrueCutMotion to remaster the 2009 film with their signature “Motion-grading” process. This technology allows filmmakers to adjust the look of motion in a film, altering the shutter angle, motion blur, and frame rate shot-by-shot. In late 2022 I got the chance to see the original Avatar in this format, as well as a personal demonstration of their toolkit, and the results are extremely intriguing.

Rereleasing the first Avatar in the months before its sequel, Cameron opted to test this variable frame rate approach, employing Pixelworks’ TrueCutMotion to remaster the 2009 film with their signature “Motion-grading” process. This technology allows filmmakers to adjust the look of motion in a film, altering the shutter angle, motion blur, and frame rate shot-by-shot. In late 2022 I got the chance to see the original Avatar in this format, as well as a personal demonstration of their toolkit, and the results are extremely intriguing.

TrueCutMotion's Motion Grading Process

TrueCutMotion claims it can utilize high frame rates while maintaining the “cinematic look”, achieving a tailored balance between the hyper clarity of high frame rates and the juddery cinematic look of 24fps.

Approaching a remaster of the 2009 Avatar meant they had to first interpolate(artificially insert frames) the film to 48fps before beginning their motion grading process. The result is extremely impressive and does not feel like an artificial interpolation.

When I saw this remastered Avatar, it used the HFR frequently but was “Motion Graded” in a way where the shift between the standard 24fps and 48fps was smooth and felt right. A good example is in the protagonist’s first experience with the bioluminescent forest, where the glassy-smooth HFR “video game” look adds an alien presence to the visuals. There are certainly some shots where the HFR-look was questionable, but it generally felt like a natural and “next-gen” addition to the film, as predicted by Trumbull years earlier.

In TrueCutMotion’s demonstration of their toolkit, I got to examine the minimal shifts in look as the dials for shutter angle, frame rate, and motion blur were adjusted. Seeing how each shot demanded specific adjustments gave me a glimpse into TCM’s vision for the future of film motion. Their tech allows for an adjustable curve between the hyper smooth HFR look and the typical juddery cinematic look, allowing filmmakers to take advantage of both, or simply to solve problems with blur at 24fps. With TCM’s toolkit, shooting a movie in HFR and reverting it back to a standard look would appear no different than if it had been captured at the standard 24fps. Whether it’s for just one blurry live-action panning shot, or a CG-animated film, this motion-grading process could pay dividends for image clarity across the industry.

After the demonstration, the Pixelworks crew urged us to see their work on the then-upcoming release of Avatar: The Way of Water, which ended up being, in my opinion, a much more frustrating motion experience than the Avatar remaster. Jarring switches between 24 and 48 frames per second resulted in two radically different looks at any given time. While I thoroughly enjoyed the HFR in the underwater scenes and during most of the action scenes, there were dozens of shots in the film where I found it massively detracted from the cinematic look.

A few months after the release of The Way of Water, in an interview with Forbes, Pixelworks’ General Manager Richard Miller clarified TCM’s work on the Avatar sequel, “With The Way of Water we came in rather late. I mean, a lot of decisions had already been made. So, in Avatar 2, from a motion perspective, you've got three types of shots. You've got shots that are double frame...they're effectively 24 frames per second. Then there are shots where the CGI and everything else was done by Weta at 48 frames per second. So, it's literally the same process that was used in Gemini Man and The Hobbit. We were brought in for shots that didn't really work in either one of those settings.”(B13)

The Way of Water had the advantage of being shot and rendered natively at 48 frames per second, which looked absolutely astonishing for the underwater scenes, but the jarring switches between a pure 48 and 24 frames per second, as well as the questionable implementation of these looks, resulted in an extremely distracting experience, especially on first viewing.

Despite my stipulations with the HFR implementation, my second viewing of The Way of Water on AMC Lincoln Square’s massive, curved IMAX screen blew my socks off. I was astounded by how much a curved screen impacted the depth of the 3D, and nullified my annoyance with the frame rates. The sense of depth was massively increased. The occasional wide-angle shots brought me into the world completely.

Avatar: The Way of Water (2022)

In perhaps my favorite visual sequence from the film, a character wakes up in an alien body before being informed that his human self is dead and that he now carries that person’s memories. This long, floaty, wide-angle shot pushes the depth of the 3D to its limit, hovering behind this character in a zero-G environment that begs comparison to the afterlife. This experience, along with many more sequences of the film, including the underwater sections, enlightened me to the transportive power of a large, curved screen, and its impact on the 3D sensation.

"I am fundamentally against flat screens. If you want a flat screen, stay home and watch television"

-Douglas Trumbull

This combination of curved screens, stereo 3D, high frame rates, large-screen-cinematography, and subjective POVs all add up to a more immersive and involving theatrical experience; vastly increasing the sense of presence the audience can absorb from a film, evoking the feeling of being mounted on a small drone, rather than looking up at a large image. Like Douglas Trumbull said when describing his Luxor hotel experiences, “You feel like you’re inside the movie. You’re not just looking at the movie, you’re in the movie.”(A8)

I hope Trumbull's story inspires us to look beyond our personal idea of cinema and embrace the future of moving images. Trumbull's end goal was to use superior technology and immersive filmmaking techniques to infiltrate the subconscious of the viewer, something Stanley Kubrick aimed to do in 1968 with 2001, and what James Cameron tried to accomplish with his Avatar movies half a century later.

For more than a decade, film pundits referred to the first Avatar film as a tech demo with a mediocre story, and blamed its overwhelming success on the trendiness of 3D, before the sequel 13 years later doubled down on its technological dependence and immersive techniques, to find overwhelming success at the box office yet again. Half a century after the release of 2001, audiences are still heading to the theater in hopes of the Ultimate Trip.

SOURCES

A1: Trumbull Cinemadaily Q+A https://cinemadailyus.com/filmmakers/qa-with-douglas-trumbull-a-special-effect-supervisor-who-worked-on-2001-a-space-odyssey-blade-runner-star-trek-the-motion-picture-and-close-encounters-of-the-third-kind/

A2: Douglas Trumbull on the Future of Film (https://youtu.be/47wO-Az22v0)

A3: Trumbull Studios: The Magi Process (https://youtu.be/JhbFrkCJ_nA)

A4: http://stevediggins.com/2014/09/10/vfx-legend-douglas-trumbull-talks-about-the-future-of-film-and-kubrick/

A5: Immersive Media Part 3 Clip (https://youtu.be/Z-glm-EFCWc)

A6: Stanley Kubrick 1968 Playboy interview (https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/movies/playboy-interview-stanley-kubrick/)

A7: Stanley Kubrick 1987 Rolling Stone Interview (https://youtu.be/ehQf0LJVOHQ)

A8: Making of the Luxor Hotel Las Vegas (https://youtu.be/GICZjTzAPBI)

A9: Remembering Douglas Trumbull (https://www.inparkmagazine.com/remembering-douglas-trumbull-part-2/)

A10: Trumbull Roger Ebert Interview 2014 (https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/the-magic-of-magi-douglas-trumbulls-quest-to-explore-a-new-planet-of-cinematic-potential)

A11: Trumbull PBS Interview (https://www.pbs.org/video/douglas-trumbull-interview-vinigy/)

A12: Trumbull Masterclass (https://youtu.be/FBaZQojd1_s)

A13: Trumbull Documentary - Film as Experience (https://youtu.be/8ZX7RynZRjU)

A14: Trumbull 2021 Indiewire Interview (https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/2001-vfx-douglas-trumbull-cgi-kubrick-1234634471/)

A15: Trumbull 2015 ParallaxView interview (https://parallax-view.org/2022/02/09/breaking-new-ground-has-always-been-in-the-medium-itself-an-interview-with-douglas-trumbull/)

A16: Trumbull Memorial Timeline (https://www.celestis.com/participants-testimonials/douglas-hunt-trumbull/)

A17: Roger Ebert on Showscan (https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/screen-gimmicks-nothing-new)

A18: Trumbull describing frame rate experiments (https://vimeo.com/674966802)

B1: Cinemacon 2011 Panel (https://youtu.be/_l9BxxPiGFY)

B2: Empire Magazine January 2022 (Page 91)

B3: AMC Laser Projection (https://investor.amctheatres.com/newsroom/news-details/2022/AMC-Theatres-Introduces-Laser-at-AMC-Powered-by-Cinionic-Ushering-in-the-Next-Evolution-of-On-Screen-Presentation/)

B4: Peter Jackson Variety Interview (https://variety.com/2013/film/news/peter-jackson-hobbit-3d-looks-1200941962/)

B5: Peter Jackson 2022 Uproxx Interview (https://uproxx.com/hitfix/peter-jackson-interview-mortal-engines-lord-of-the-rings/)

B6: James Cameron on Gemini Man HFR (https://collider.com/avatar-sequels-no-hfr-james-cameron/)

B7: Ang Lee Experience on Life of Pi (https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/gemini-man-ang-lee-interview-promise-digital-hfr-3d-cinema-1202180316/)

B8: Ang Lee Interview on Billy Lynn 2016 (https://deadline.com/2016/05/ang-lee-billy-lynns-long-halftime-walk-cannes-disruptor-interview-1201752479/)

B9: Trumbull filmmaker magazine interview (https://filmmakermagazine.com/102741-interview-douglas-trumbull-2017/)

B10: Peter Jackson The Hobbit BTS (https://youtu.be/20vA9U7J2qQ)

B11: James Cameron on getting off 24fps (https://youtu.be/cMm9nZxOaE8)

B12: James Cameron on Avatar 2 HFR (https://youtu.be/coIfiKxCahk)

B13 : TrueCutMotion Forbes interview (https://www.forbes.com/sites/bennyhareven/2023/02/27/can-avatar-the-way-of-waters-truecut-motion-tech-save-high-frame-rate-cinema/?sh=7a253a4f43f9)

B14: Trumbull on The Hobbit (https://www.cnn.com/2013/05/13/tech/innovation/douglas-trumbull-interview/index.html)

B1: Cinemacon 2011 Panel (https://youtu.be/_l9BxxPiGFY)

B2: Empire Magazine January 2022 (Page 91)

B3: AMC Laser Projection (https://investor.amctheatres.com/newsroom/news-details/2022/AMC-Theatres-Introduces-Laser-at-AMC-Powered-by-Cinionic-Ushering-in-the-Next-Evolution-of-On-Screen-Presentation/)

B4: Peter Jackson Variety Interview (https://variety.com/2013/film/news/peter-jackson-hobbit-3d-looks-1200941962/)

B5: Peter Jackson 2022 Uproxx Interview (https://uproxx.com/hitfix/peter-jackson-interview-mortal-engines-lord-of-the-rings/)

B6: James Cameron on Gemini Man HFR (https://collider.com/avatar-sequels-no-hfr-james-cameron/)

B7: Ang Lee Experience on Life of Pi (https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/gemini-man-ang-lee-interview-promise-digital-hfr-3d-cinema-1202180316/)

B8: Ang Lee Interview on Billy Lynn 2016 (https://deadline.com/2016/05/ang-lee-billy-lynns-long-halftime-walk-cannes-disruptor-interview-1201752479/)

B9: Trumbull filmmaker magazine interview (https://filmmakermagazine.com/102741-interview-douglas-trumbull-2017/)

B10: Peter Jackson The Hobbit BTS (https://youtu.be/20vA9U7J2qQ)

B11: James Cameron on getting off 24fps (https://youtu.be/cMm9nZxOaE8)

B12: James Cameron on Avatar 2 HFR (https://youtu.be/coIfiKxCahk)

B13 : TrueCutMotion Forbes interview (https://www.forbes.com/sites/bennyhareven/2023/02/27/can-avatar-the-way-of-waters-truecut-motion-tech-save-high-frame-rate-cinema/?sh=7a253a4f43f9)

B14: Trumbull on The Hobbit (https://www.cnn.com/2013/05/13/tech/innovation/douglas-trumbull-interview/index.html)

B15: James Cameron sci fi documentary (https://youtu.be/gyHcLOnLilM @ 0:25)

B16: James cameron on 2001 (https://youtu.be/dkHeJOFsQPc @ 19:00)

.png)

.png)